Contrary to what you might wish were true, if you take the time to think about it, the people who make the best torturers and death squad leaders aren't deviants. Research has demonstrated that they aren't sadists, and they don't have a predilection for hurting others. If only they had some sort of identifiable mental aberration, we might be able to shield ourselves from the fact that you and I, in the right situation, could feel good about peeling the skin off someone as they screamed and begged for mercy.

To me, the most unsettling thing about our universal weakness is the demonstrated fact that people who are familiar with the phenomena are themselves just as likely to do horrible things when the situation demands it of them and to miss seeing that they have been inadvertently manipulated by the situational influences to condone and/or commit evil acts. Philip Zimbardo's "Stanford Prison Experiment" is a case in point.

The situations that compel participation, compliance, and complicity have some common elements. These elements have been enumerated by a number of social scientists over the past years, particularly since, and as a result of, the behavior of so many people associated with the Nazis.

One of the well known early works was Hannah Arendt's Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, from 1963. In certain situations, doing otherwise horrible things becomes so common place that no one even notices it any longer. It becomes normal behavior. The evil is normalized.

This normalization of evil is a common factor in situations that condone and reward behaviors that would otherwise be immediately recognized as cruel or even criminal.

Another common factor in such situations is that otherwise aberrant behaviors are promoted and condoned by authorities. This is particularly true when the authority is the State. This seems to be related to our propensity to arrange our values in a way that puts the opinions of authority figures ahead of what we believe is right behavior if asked about our ethical beliefs in a neutral setting. This particular common psychological phenomena seems also related to our natural moral development. These characteristics have been looked at carefully by a number of social scientists. See for instance Stanley Milgram's Obedience to Authority and Lawrence Kohlberg's "Stages of Moral Development."

A third factor is the use of the term war or the designation of a common enemy. The War on Terrorism, the War on Crime, the War on Drugs, or common enemies: Communists, socialists, or enemies of the State; these are examples of the sort of branding that can contribute to otherwise decent people doing things that they would never do if not confronted by an apparent emergency or immanent threat.

The influence of the State, its power to declare war and identify the common enemy, to determine what is and isn't legal and moral, has a profound influence over us. In The Nazi Doctors, Robert J. Lifton writes at some length about the doctors who made the selections at Auschwitz. These too were otherwise reasonably decent people. They needed emotional support and reassurance early on to get over their discomfort with being the ones who decided who would die right away and who would live a little while longer. But, evil was the norm, they were at war, they were working for the State, and they were "treating" the nation against a common enemy.

As I was writing this, I heard a news story about New Yorker staff writer Sarah Stillman receiving a 2013 George Polk Award, a prestigious annual award for journalism, for her article, "The Throwaways." She reported on law enforcement’s unregulated use of young confidential informants in drug cases. The War on Drugs and the situational influences that surround it explain why otherwise reasonably decent people, police officers in this case, are willing to exploit children and force them into dire situations that end up occasionally being fatal encounters with hardened criminals.

I suspect that the law enforcement officials involved are sorry for the children and others they coerce into becoming undercover informants, particularly when they are physically harmed or killed, but hey, sacrifices must be made, we are at war.

When these three elements come together, the likelihood of people doing horrible things increases dramatically. It becomes a near certainty that any ugliness will increase unabated until something revolutionary stops it: a political coup, being defeated in war, or some more powerful outside influence forcing a change.

This last possibility seems to be possible only when the situation is unique to some subunit of some structured hierarchy like a rogue police precinct or a military unit that has lost track of basic norms.

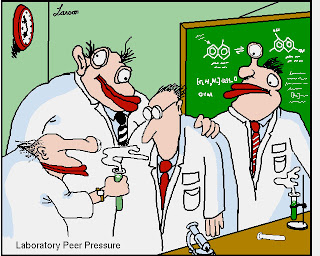

These three elements: the normalization of evil; encouragement, support and reward for the evil acts by the authorities or State; and the designation of a common enemy, in this case disease or imperfect knowledge of biology, have combined synergistically to produce the bureaucratic system -- the situational influence -- that supports, works to expand, and defends any and all uses of animals in publicly-funded scientific research.

Those within the system behave exactly as social scientists would predict most people operating within such a system will behave. Otherwise decent people are compelled to be cruel. Otherwise decent people are compelled to approve the cruelty. Otherwise decent people are compelled to defend the cruelty. And otherwise decent people are compelled to lie, mislead, dissemble, censor, and obfuscate to protect the system and their comrades within the system.

How far removed from the actual act does someone have to be before they can claim some immunity from responsibility?

It seems to me that someone who was a member of the Nazi Party wasn't necessarily complicit in the Holocaust. An employee of the U.S. government is not necessarily responsible for blowing up an Afghani wedding party with a drone attack. But somewhere up the line or off to the side, people not directly involved do bear some responsibility, and the ethical weight of that responsibility seems to increase along with the knowledge of what their employer is doing.

It seems to me that someone who was a member of the Nazi Party wasn't necessarily complicit in the Holocaust. An employee of the U.S. government is not necessarily responsible for blowing up an Afghani wedding party with a drone attack. But somewhere up the line or off to the side, people not directly involved do bear some responsibility, and the ethical weight of that responsibility seems to increase along with the knowledge of what their employer is doing.It seems to me also that the more one relies on the spoils of an employer's evil deeds while knowing where the money comes from, the more responsible one becomes. In many, maybe most cases, this responsibility may not carry with it the ability to do anything about the acts, but it does seem to require an overt distancing of oneself from the deeds, either with public comments (comments, not a single comment) or finding other employment. The more one knows, the more one's silence becomes an act of complicity.

So what about university employees and students? Which of them bear some responsibility for the evil things done to animals that has become normalized in the laboratories, the evil things that are done to animals in the name of Science, the War on Disease, the evil things that are sanctioned, condoned, and paid for by their institution and the State?

My observations regarding personal responsibility notwithstanding, the actual case is much different, as so much social science points out. The reality is that the closer one gets to the atrocities, the more one is controlled by the situation; the more one is distanced, the more one will deny a responsibility. The status quo is maintained. And thus, Germans rounded up and killed millions of people they saw as unlike themselves; Stalin massacred millions more; Americans tortured and killed prisoners at Abu Ghraib, and people who claim to be aware of the very serious risks of situational influences get swallowed by the system and don't even know they are being digested. They probably don't even understand this reference to them.

No comments:

Post a Comment